- Home

- Shoulder Anatomy

- Shoulder Joints

Shoulder Joint Anatomy

Written By: Chloe Wilson BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy

Reviewed By: SPE Medical Review Board

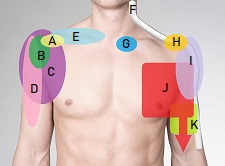

Shoulder joint anatomy refers to four different joints in and around the shoulder.

The glenohumeral joint links the upper arm to the shoulder blade.

The acromioclavicular joint links the shoulder blade to the collar bone.

The sternoclavicular joint links the collar bone to the chest bone and the scapulothoracic joint links the shoulder blade to the thorax.

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the entire body which comes about from the complex combination of movement through all four joints. This is controlled by a number of different muscles acting on the different shoulder joints providing huge shoulder range of motion.

Each joint allows for movement in different directions, and when these movements combine, we can perform a whole range of movements and functions with the upper arm, such as throwing, lifting, carrying, pushing, pulling and reaching behind our back.

Shoulder Joint Anatomy & Function

Here we will look at the shoulder joint anatomy for each of the four joints, how they function and what can go wrong.

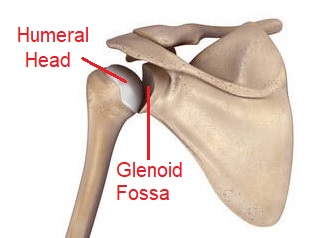

1. Glenohumeral Joint Anatomy

The glenohumeral joint is the main joint of the shoulder region. When people talk about “the shoulder”, what they usually mean is the glenohumeral joint.

With glenohumeral shoulder joint anatomy, we are talking about the joint between the:

- Humerus: upper arm bone

- Scapula: shoulder blade

The glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket joint. The “ball” is formed by the head of humerus, a hemispherical portion that angles out and up from the top of the humerus towards the body.

The “socket” is formed by a concave depression on the upper, outer border of the scapula, known as the glenoid cavity or glenoid fossa. The socket is very shallow and fairly flat.

The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile joint in the whole body due its shape. The surface area of humeral head is 3-4x greater than the shallow glenoid cavity socket, meaning there is little contact area between the bones, so the joint offers little bony stability.

Whilst this structure of glenohumeral shoulder joint anatomy is excellent for mobility (think how much movement there is in your upper arm), it makes the joint very unstable and prone to injury.

The glenohumeral joint combats this by gaining stability from a network of soft tissues:

- Labrum: the glenoid labrum is a rim of cartilage that lines the edge of the glenoid cavity to deepen the socket

- Joint Capsule: the joint capsule is like a bag that wraps around the glenohumeral joint, enveloping it. However the capsule itself is very loose to allow for the great range of movement so only provides minimal stability. It is however supported by various tendons and ligaments which help to increase joint stability

- Muscles: the glenohumeral joint is surrounded by a number of muscles that provide stability to the joint. The main stabilising muscles are rotator cuff, a group of four muscles that surround the joint, providing both static and dynamic stability

The glenohumeral joint is referred to as a multiaxial joint in shoulder joint anatomy meaning it can move in multiple directions – flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, being able to move through a large range in each direction.

Common Problems

The lack of stability in shoulder joint anatomy makes the glenohumeral joint prone to injuries including:

- Rotator Cuff Injuries: tearing of one (or more) of the rotator cuff tendons

- Impingement Syndrome: Narrowing of the subacromial space at the top of the shoulder damages the soft tissues

- Frozen Shoulder: Inflammation and tightening of the joint capsule

- Labrum Tears: damage to the cartilage lining rim of the shoulder socket

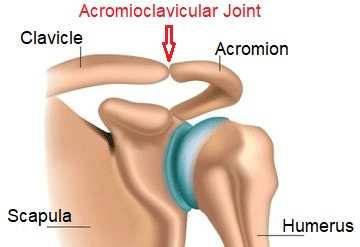

2. Acromioclavicular Joint Anatomy

The second area in shoulder joint anatomy is the acromioclavicular joint, the joint between the shoulder blade and the collar bone.

The acromioclavicular joint is the junction between the:

- Acromion Process: the bony projection at the upper tip of the shoulder blade

- Clavicle: the outer potion of the collar bone

The acromioclavicular joint is a plane, synovial joint and the ends of the acromion and clavicle are held together by a joint capsule that is supported by ligaments. This structure allows a small amount of gliding movement between the bones and provides good stability to the acromioclavicular joint.

The acromioclavicular joint is a multiaxial joint that allows movement in three planes – protraction/retraction, elevation/depression and rotation.

The main functions of the acromioclavicular joint are to:

- Provide stability and motion to the shoulder complex

- Assist scapula movement which increases shoulder mobility

- Transmit forces between the upper limb and the trunk

One important aspect shoulder joint anatomy here that affects arm movement is the size and shape of acromioclavicular joint. The shape and angle of the articular surfaces (the ends of the bones), known as facets, vary from person to person. The facets may be flat, concave (rounded inwards) or convex (rounded outwards) in any combination.

The different shapes of the ends of the bones affect how much wear and tear there is on the acromioclavicular joint surfaces and can make you more or less prone to shoulder injuries.

Common Problems

Injuries to the acromioclavicular joint are common, accounting for around 40% of all shoulder injuries. The most common injuries are ligament injuries, joint separation, ACJ dislocation and arthritis.

3. Sternoclavicular Joint Anatomy

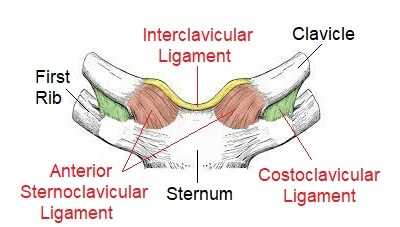

Another part of shoulder joint anatomy is the sternoclavicular joint, a synovial saddle joint between the:

- Sternum: chest bone

- Clavicle: collar bone

The sternoclavicular joint is a very strong and mobile joint and acts as a pivot for shoulder movements.

The main role of the sternoclavicular joint is to co-ordinate movement between the shoulder girdle and the trunk to allow for full range of motion in the upper limb. Similar to the glenohumeral joint, there is little bony stability at the sternoclavicular joint as the convex end of the clavicle is larger than the concave surface on the sternum.

The joint capsule and ligaments are important parts of sternoclavicular joint anatomy as they are the main stabilising structures of the joint. There main ligaments when looking at sternoclavicular joint anatomy:

- Anterior and Posterior Sternoclavicular Ligaments: broad ligaments found at the front and back of the joint

- Interclavicular Ligament: links the two collar bones together running over the top of the sternum

- Costoclavicular Ligament: runs between the top of the first rib and the bottom end of the collar bone

The sternoclavicular joint plays an important role in shoulder movements, contributing to

- Elevation/Depression: 40 degrees of movement

- Protraction/Retraction: 35 degrees of movement

- Axial Rotation: 20-40 degrees of movement

Almost any movement of the upper arm requires some movement at the sternoclavicular joint – you can feel this if you put your fingers over the joint and move your arm.

Whilst sternoclavicular joint anatomy allows for a good range of motion, there are no muscles that actually produce movement directly at the joint. Instead, joint movement is caused by movement of the clavicle in response to scapula and shoulder girdle movement.

Common Problems

The sternoclavicular joint ligaments are so strong that there is a high chance that the collar bone with break before the ligaments will tear with shoulder injuries. Clavicle fractures are actually the most common type of fracture in children.

Sternoclavicular joint dislocations are however rare as it takes a significant force to dislocate the joint due to the strong ligaments, with anterior dislocations being nine times more common than posterior dislocations. Sternoclavicular arthritis causes wear and tear at the joint which can result in pain and impaired movement.

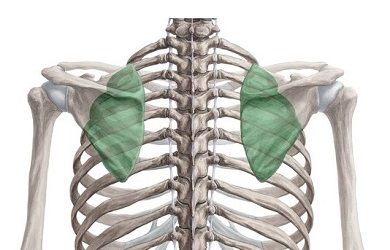

4. Scapulothoracic Joint Anatomy

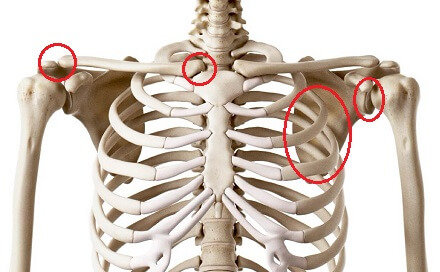

The final element in shoulder joint anatomy is the scapulothoracic joint at the back of the shoulder. The scapulothoracic joint plays a huge role in shoulder and arm movement and stability.

The scapulothoracic joint, aka scapulocostal joint is a sliding “joint” between the:

- Scapula: anterior surface of the shoulder blade

- Thorax: posterior wall of the rib cage

However, the specific scapulothoracic joint anatomy means it is not actually a “true” anatomical joint as there is no direct articulation between bones, any connecting ligaments or a joint capsule. It is given joint status though as the junction between the shoulder blade and the chest wall.

The shoulder blade is the large flat, triangular bone that rests on the back of the second to eighth ribs about 2 inches out from the spine. The thorax and scapula bones don’t actually articulate with each other (i.e. they don’t touch), they are separated by the subscapularis and serratus anterior muscles.

The scapula is like the link bone between the other parts of the shoulder, and the scapulothoracic joint is closely linked with the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint. Any movement of the scapula produces movement at one or both of these shoulder joints. As the shoulder blade glides over the chest wall, it pivots around the acromioclavicular joint and allows the shoulder to move into the correct position.

Scapulothoracic joint anatomy makes the joint an important component of both:

- Scapulohumeral Rhythm: The combination of movement between the glenohumeral joint and scapulothoracic joint is known as scapulohumeral rhythm and allows for efficient arm movement. Shoulder movements occur at a ratio of approximately 2:1 glenohumeral joint : scapulothoracic joint e.g. with shoulder flexion, 100-120 degrees comes from the glenohumeral joint, 50-60 degrees comes from the scapulothoracic joint

- Shoulder Stability: The scapula provides a stable base for the shoulder to move from thanks to the action of a number of different muscles. Without adequate scapular stabilisation, the glenohumeral joint can’t move efficiently which can limit arm movement, strength and function, and increase the risk of injury.

The movements performed at scapulothoracic joint are: protraction/retraction, elevation/depression, anterior/posterior tilt, internal/external rotation and upward/downward rotation.

The scapular stabilising muscles (trapezius, rhomboids and serratus anterior) work with the main shoulder stabilising muscles (rotator cuff) to anchor the shoulder blade and guide shoulder movement.

Common Problems

There are lots of different causes of shoulder blade pain. The most common problem associated with scapulothoracic joint anatomy is impaired scapulohumeral rhythm usually due to muscle imbalance. This can lead to shoulder impingement syndrome, tendonitis, scapulothoracic bursitis and increase the risk of rotator cuff tears.

The best way to improve scapulohumeral is with stabilization exercises.

Shoulder Joint Anatomy Summary

The shoulder is made up of four joints:

- Glenohumeral Joint: synovial ball and socket joint between the head of humerus and glenoid cavity

- Acromioclavicular Joint: synovial plane joint between the acromion and clavicle

- Sternoclavicular Joint: synovial saddle joint between the sternum and clavicle

- Scapulothoracic Joint: false joint between the scapula and thorax

Movement occurs in combination at all four joints to allow for the huge range of motion at the shoulder.

What the shoulder lacks in bony stability, it makes up for through a combination of stabilising muscles (rotator cuff and scapular stabilisers), joint capsule, glenoid labrum, ligaments and cartilage.

Shoulder injuries are common and can occur in any of the joints and surrounding soft tissues, resulting in pain and restricted movement and function.

If you want to find out more about shoulder joint anatomy and function, check out the following articles:

Related Articles

Shoulder Problems

November 6th, 2024

Diagnosis Charts

February 11th, 2025

Rehab Exercises

December 12, 2023

Page Last Updated: November 5th, 2024

Next Review Due: November 5th, 2026