- Home

- Shoulder Anatomy

- Shoulder Ligaments

Shoulder Ligaments

Written By: Chloe Wilson BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy

Reviewed By: SPE Medical Review Board

The shoulder ligaments are tough, elastic bands of connective tissues.

They connect bone to bone, support the shoulder joints and limit their movement, playing a vital role in passive shoulder stability.

The shoulder is made up of a number of different joints, and each of these joints are supported by a number of ligaments.

The shoulder ligaments help to reinforce and support the joint capsules, draw the bones together and resist dislocation.

Ligaments are made up of tough bands of fibrous connective tissue that contain strong collagen fibres. As we age, the collagen fibres in ligaments change from being wavy to being straight, which makes them less elastic and stiffer, and therefore more prone to damage.

Here we will look at the different shoulder ligaments, where they are, how they work, why they are so important and what can go wrong.

Shoulder Joint Ligaments

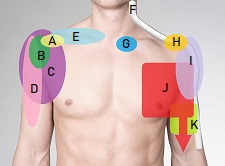

The shoulder ligaments work together to connect the humerus (upper arm bone), scapula (shoulder blade), clavicle (collar bone) and sternum (breast bone) through a series of joints:

- Glenohumeral Joint: a ball and socket joint between the humeral head and the glenoid fossa (part of the scapula). More commonly referred to as the shoulder joint

- Acromioclavicular Joint: the joint between the acromion (part of the shoulder blade) and the clavicle

- Sternoclavicular Joint: the joint between the clavicle and the sternum

Any movement of the arm, particularly above head height involves movement at each of these joints and the shoulder ligaments play an important role in controlling the movement.

So let’s look at the nine main shoulder ligaments, where they are and what they do.

1. Glenohumeral Ligaments

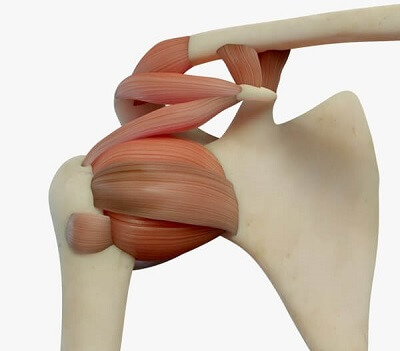

The glenohumeral ligaments are one of the most important group of shoulder ligaments at the glenohumeral joint.

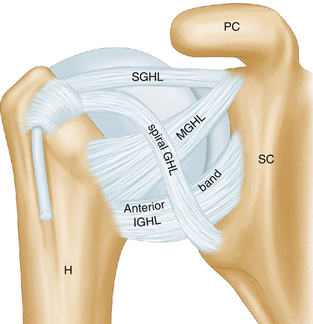

There are four glenohumeral ligaments found on the front of the shoulder joint, the superior glenohumeral ligament, medial glenohumeral ligament, the inferior glenohumeral ligament and the spiral glenohumeral ligament, but not everyone has all four.

They connect the humerus bone to the glenoid cavity on the scapula bone in various different places.

Function: the glenohumeral ligaments help to reinforce the glenohumeral joint capsule and improve stability at the front of the joint, particularly with shoulder abduction, adduction and external rotation. All four ligaments help reduce the risk of anteroinferior shoulder dislocation.

Superior Glenohumeral Ligament (SGHL)

Origin: apex (top) of the glenoid fossa near the root of the coracoid process

Insertion: upper portion of the lesser tubercle of the humerus

Special Features: Stabilises the biceps brachii tendon. Present in 98% of the population

Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament (IGHL)

Origin: inferior (lower) edge of the glenoid fossa

Insertion: anatomical neck of the humerus, just above the lesser tuberosity

Special Features: Strongest of the four glenohumeral ligaments and the main stabiliser of the shoulder when it is abducted. Present in 94% of the population

Medial Glenohumeral Ligament (MGHL)

Origin: medial (inner) edge of the glenoid fossa

Insertion: lower part of the lesser tubercle of the humerus

Special Features: aka Middle Glenohumeral Ligament. Present in 88% of the population.

Spiral Glenohumeral Ligament (SpGHL)

Origin: infraglenoid tubercle

Insertion: less tubercle of the humerus with subscapularis tendon

Special Features: Reinforces the anterior joint capsule. The spiral ligament is the least common glenohumeral ligament, only found in around 45% of the population

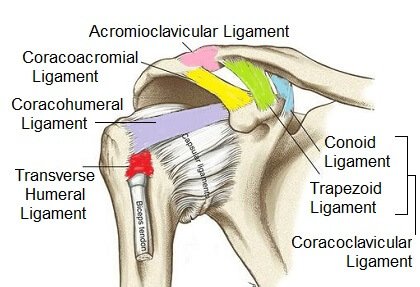

2. Coracohumeral Ligament

The coracohumeral ligament (CHL) is a broad shoulder ligament divided into two bands, the superior and inferior bands.

Function: the coracohumeral ligament reinforces and strengthens the upper part of the glenohumeral joint capsule, and protects the head of humerus.

Superior Band

Origin: lateral (outer) border of the base of the coracoid process

Insertion: greater tubercle of the humerus with supraspinatus tendon

Inferior Band

Origin: lateral surface of the base of the coracoid process

Insertion: lesser tubercle of the humerus

3. Acromioclavicular Ligament

The acromioclavicular jligament (ACL) runs horizontally, connecting the shoulder blade and collar bone. It has two parts, the superior acromioclavicular ligament and the inferior acromioclavicular ligament.

Function: The acromioclavicular ligament reinforces the superior (upper) portion of the joint capsule and provides horizontal stability at the AC joint

Superior Acromioclavicular Ligament

Origin: Superior (upper) surface of the acromion

Insertion: lateral (outer) end of the clavicle

Inferior Acromioclavicular Ligament

Origin: inferior (lower) surface of the acromion

Insertion: lateral end of the clavicle

4. Coracoclavicular Ligament

The coracoclavicular ligament (CCL) also connects the shoulder blade to the collar bone. It is made up of two small, but strong parts, the conoid ligament at the back and the trapezoid ligament at the front. The conoid ligament, shaped like an inverted cone, lies medial to the thinner trapezoid ligament.

Function: The coracoclavicular ligament is extremely strong, carries a large load and keeps the scapula attached to the clavicle which provides the square shape to your shoulders. It provides vertical stability at the ACJ and transmits weight from the upper limb to the axial skeleton.

Conoid Ligament

Origin: posterior surface and root of the coracoid process of the scapula

Insertion: conoid tubercle on the inferior surface of the clavicle

Trapezoid Ligament

Origin: superior (upper) surface of the coracoid process

Insertion: trapezoid line on the under surface of the lateral clavicle

5. Coracoacromial Ligament

One of the major shoulder ligaments, the coracoacromial ligament (CAL), is a strong triangular shaped ligament. It connects two parts of the scapula forming an arch over the top of the glenohumeral joint known as the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff tendons and subacromial bursa run under this arch.

Function: The coracoacromial shoulder ligament protects the head of humerus, increases shoulder stability and prevents superior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. It also transmits loads across the scapula

Origin: lateral border of the coracoid process

Insertion: inferior anterolateral surface of the acromion

Thickening of the coracoacromial ligament often results in impingement syndrome as it reduces the subacromial space.

6. Transverse Humeral Ligament

The transverse humeral ligament (THL), aka Brodie’s Ligament, is slightly different to the other shoulder ligaments as it doesn’t cross a joint. Instead it spans the gap between the greater and lesser tubercles at the humeral head

Function: The transverse humeral ligament holds the long head of biceps tendon into position in the intertubercular groove.

Origin: Greater tubercle of the humerus

Insertion: Lesser tubercle of the humerus (intertubercular sulcus)

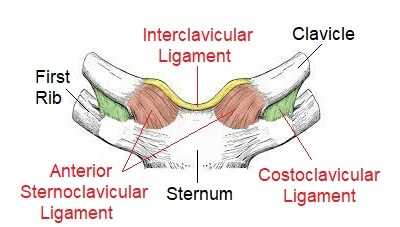

7. Sternoclavicular Ligaments

The sternoclavicular ligaments (SCL) connects the collar bone with the breast bone.

There are two parts to this shoulder ligament, the anterior sternoclavicular ligament, and the posterior sternoclavicular ligament, found at the front and back of the joint respectively.

Function: The sternoclavicular ligaments reinforce the joint capsule and help to stabilise the sternoclavicular joint. They limits anterior/posterior translation of the clavicle i.e. stop it moving too far forwards and backwards

Anterior Sternoclavicular Ligament

Origin: medial end of the clavicle

Insertion: Anterosuperior manubrium on the sternum

Special Features: limits excess superior displacement at the joint and resists upward rotation and lateral movement of the clavicle

Posterior Sternoclavicular Ligament

Origin: posterior surface (back) of the sternal end of the clavicle

Insertion: Posterosuperior manubrium

Special Features: resists downward rotation and medial movement of the clavicle

8. Costoclavicular Ligament

The costoclavicular ligament (CCL) connects the first rib to the collar bone and is a short, flat but very strong ligament. It is also known as Halsted’s Ligament or the rhomboid ligament due to its shape.

Function: The Costoclavicular ligament is the main stabilising structure of the sternoclavicular joint, reinforcing the inferior aspect underneath the sternoclavicular joint. It limits clavicle and shoulder girdle elevation and anteroposterior movement (forwards and backwards) at the sternoclavicular joint

Origin: superior (upper) surface of the 1st rib and its cartilage

Insertion: costal tuberosity on the inferomedial aspect of the clavicle

9. Interclavicular Ligament

The interclavicular ligament (ICL) is a flattened band that spans the gaps between the both clavicles running along the upper surface of the sternoclavicular joint.

Function: The interclavicular shoulder ligament reinforces the top part of the sternoclavicular joint capsule. It resists excessive downward glide and clavicular dislocation with shoulder depression

Origin: Upper part of the sternal end of one clavicle

Insertion: Upper part of the sternal end of the other clavicle

Shoulder Ligament Injuries

Shoulder ligaments are prone to damage. Anything that causes them to stretch beyond their elastic limit will cause them to tear, and repetitive friction on the shoulder ligaments can cause them to become inflamed and fray.

What Causes Shoulder Ligament Injuries?

Most shoulder ligament injuries are caused by either:

- Direct Trauma: to the shoulder e.g. fall. Most common in younger people

- Repetitive Friction: on the ligament e.g. from frequent overhead activities, which leads to inflammation and wear and tear. Most common in people over the age of 60.

Shoulder ligament injuries are often associated with other shoulder injuries such as:

- Shoulder Bone Injuries: fractures or dislocations

- Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: narrowing of the subacromial space

- Labrum Tears: damage to the special ring of cartilage on the shoulder socket

Symptoms Of Ligament Tears

Common symptoms of shoulder ligament injuries include:

- Shoulder Pain: pain gets worse with arm movements particularly raising your arm above your head or shrugging your shoulders

- Inflammation: and swelling around the shoulder

- Limits Daily Activities: due to pain and resultant stiffness. May also affect sleep

- Instability: the shoulder may feel weak. People with shoulder ligament injuries often say they don’t trust their shoulder and feel like it is going to pop out.

- Deformity: obvious visual deformity at the affected shoulder joint if the ligament has completely ruptured

The symptoms will depend on which shoulder ligament is involved, the severity of the damage and whether any other structures are involved.

Classification & Treatment

Shoulder ligament tears can be classified into three categories:

- Grade 1: Minor tearing of one or more shoulder ligaments – less than 10% of fibres. Self-treat with rest, ice and over the counter medication. Usually heals in 3-6 weeks

- Grade 2: Partial or incomplete tear of one or more of the shoulder ligaments. May need to wear a sling for a few weeks. Usually heals in 6-12 weeks

- Grade 3: Complete tear or rupture of the shoulder ligament. May require arthroscopic (keyhole) surgery to repair or reattach the ligament

With shoulder ligament injuries, it is vital to rebuild the stability at the shoulder to reduce the risk of further injury. One of the best ways to do this is with a rehab program that focuses on:

- Rotator Cuff Strengthening: exercises to improve the active stability at the shoulder from the rotator cuff muscles

- Scapular Stabilisation: exercises to improve the stability and control around the shoulder blade

Shoulder Ligaments Summary

The shoulder ligaments are the main structures that provide passive stability at the shoulder. There are nine shoulder ligaments that work together to:

- Stabilize the shoulder

- Reinforce joint capsules

- Hold the shoulder in place

- Reduce risk of shoulder dislocation

- Limit bone movement at the joints

Shoulder ligament injuries are common and in most cases can be treated at home with rest, ice, medication and exercises.

If you want like to find out more about the other structures in and around the shoulder, visit the anatomy of the shoulder section.

If you are suffering from shoulder pain but don't think it is from the shoulder ligaments, check out the shoulder pain diagnosis section for help working out what is wrong.

Related Articles

Pain At Night

November 5th, 2024

Diagnosis Charts

February 11th, 2025

Rehab Exercises

December 12, 2023

Page Last Updated: November 5th, 2024

Next Review Due: November 5th, 2026